Abortion is traditional healthcare. The Blackfeet performed abortions for thousands of generations before Roe v Wade or six week “heartbeat” bans. I knew all of this. Yet as I sat in the clinic in the West Loop in Chicago, I was terrified. I hadn’t understood what an abortion was until the previous week or so, when I was frantically reading through infographics online.

Missouri, where I lived at the time, had restrictive laws on abortion and only one abortion clinic, a Planned Parenthood a few blocks from my apartment that always had protestors. At the time, after you got an ultrasound, you were required to wait three days before getting an abortion. I decided to go across the border to Illinois instead. I called Planned Parenthood, since I used to go to one near Clark and Division when I lived in Chicago. There were no appointments in the time frame I needed; there were no appointments at any Planned Parenthood in the state in the time frame I needed. So here I was, at a clinic I had never been to in a neighborhood I rarely frequented. Three hundred miles from home.

A friend flew up from Texas. She was sitting next to me in the waiting room, her leg shaking violently. Maybe she was nervous too. I wanted to tell her to stop, she was shaking the whole bench and it wasn’t helping my nerves. But I didn’t want to be rude. So I sat there, staring at all the other women and couples in the waiting room.

First, I got an ultrasound to figure out how far along I was. The doctor, a white lady with warm hands whose face I don’t remember, said I didn’t have to look if I didn’t want to. I glanced over quickly. I was ten weeks along, but if you had shown me a picture of my uterus and someone else's who wasn’t pregnant, I wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference. There was no discernable shape. I felt a sense of relief.

“Since you’re about ten weeks along, you can get a medication abortion,” she told me.

She explained that I would be given two pills: one to take right now, at the clinic, and another to take tomorrow. I’d also get extra-strength pain killers, and a prescription for more if I needed them. She asked if I had anything to do tomorrow, because it’s best to stay home when you take the second pill. I lied and said no, I didn’t have anything to do.

I went to three different rooms in the clinic: the ultrasound room, another room where my vitals were checked, and finally a cubicle in the front office, where I signed some forms and got the pills. My graduate student insurance didn’t cover it, so I paid $500 out of pocket. Almost the same as the rent in my studio apartment.

In 2015, I was working for a member of Congress when doctored videos about Planned Parenthood’s donation of fetal tissue, a practice commonly used in medical research with decades of bipartisan support, went viral. Since I was an underling in the office, I was the first line of defense on the phones. The Congresswoman I worked for represented a fairly liberal, educated, middle class district. Of course, we always had some wacky callers. Most I was sympathetic to; I nodded along, assuming they had no one to rant to about politics. This changed when Planned Parenthood was under attack. Jason Chaffitz, who was then chair of the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee, was constantly on the TV in our office. Two different people called the Congresswoman concerned that Planned Parenthood was selling babies as dog food to China. I thanked them for calling, and hung up.

Around the same time, the first Planned Parenthood clinic was being built in Washington, DC. It was right next to where my boss’ kids went to elementary school. He was infuriated almost every day after dropping his kids off. The clinic hadn’t even opened yet and there were constantly protestors outside. They screamed at the children as they walked into school that a child killing factory was opening next door. He said that a lot of the protestors weren’t local DC residents, but people coming specifically to protest the clinic.

We weren’t allowed to wear our pink Planned Parenthood pins around constituents.

The day after I took the pills, I spent hours on the toilet, puking and getting diarrhea and bleeding. I had only puked three times before in my life. Most of my memories of that Christmas revolve around bleeding. When I look at photos all I can think of is how uncomfortable I was and how I was afraid of bleeding through my ultra-thick pads. Luckily, that only happened once. In early January, I bled through my pad, underwear, and clothes. I cleaned myself as best I could and took an Uber home with a friend. For what felt like hours, I stood in the shower and bled. Chunks came out that were too thick to go down the mesh covered drain. An indiscernible mess of blood and uterine lining, like my ultrasound. I pressed on it with my toes.

“This is my punishment for premarital sex,” I joked to my friend, when I was finally out of the shower and into clean clothes.

“You’re not being punished,” she responded, solemnly. She didn’t laugh.

That night, as my friend and I watched The Haunting of Hill House, I texted the guy that I’d recently broken up with that I’d had an abortion. I said it was $500 and insurance wasn’t covering it, hoping he would offer to pay half. I was a grad student, he was an engineer. He thanked me for telling him. We didn’t speak for another month.

When I returned to the clinic in Chicago for my final ultrasound before going back to school, volunteers met me at the corner and walked me to the door. They said nothing to me. I thanked them. I sat in the waiting room alone. This time, I was the one shaking the bench with my agitated leg. I wondered how my relatives and ancestors may have experienced this process differently.

In the 1970s, John C. Hellson and Morgan Gadd interviewed Blackfoot elders on ethnobotany. Many of the elders were born in the 1800s or the turn of the century and grew up knowing traditional plant uses. This was the first Western attempt to record Blackfoot plant use by interviewing knowledgeable Blackfoot people.

At the time Hellson and Gadd were conducting interviews, abortion was illegal in Canada. Yet the elders they interviewed spoke about using at least 11 plants used for childbirth, three for abortions, and two for menstruation, as well as medicine bundles to increase fertility. They had deep knowledge of reproductive medicine.

Physically, my experience was likely similar to that of my ancestors. But I wondered how my experience was different socially, culturally, politically. What care they would have received from the medicine women in their families and communities. Who might have kissed them on the forehead and helped them clean themselves of blood.

Even with all my privileges — the ability to pay $500, to drive five hours to a clinic in a different state, to navigate clinic websites and phone lines in English, to access abortion when it was legal across the nation — getting an abortion was an awful experience. For me, it was physically painful, embarrassing, and felt shameful.

Interestingly, when I think about my abortion today, the guy I’d had sex with isn’t a part of the story. We’d broken up by the time I found out. I texted him once to let him know.

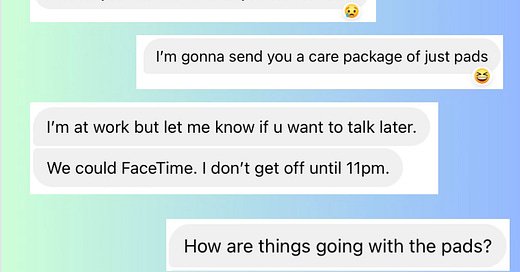

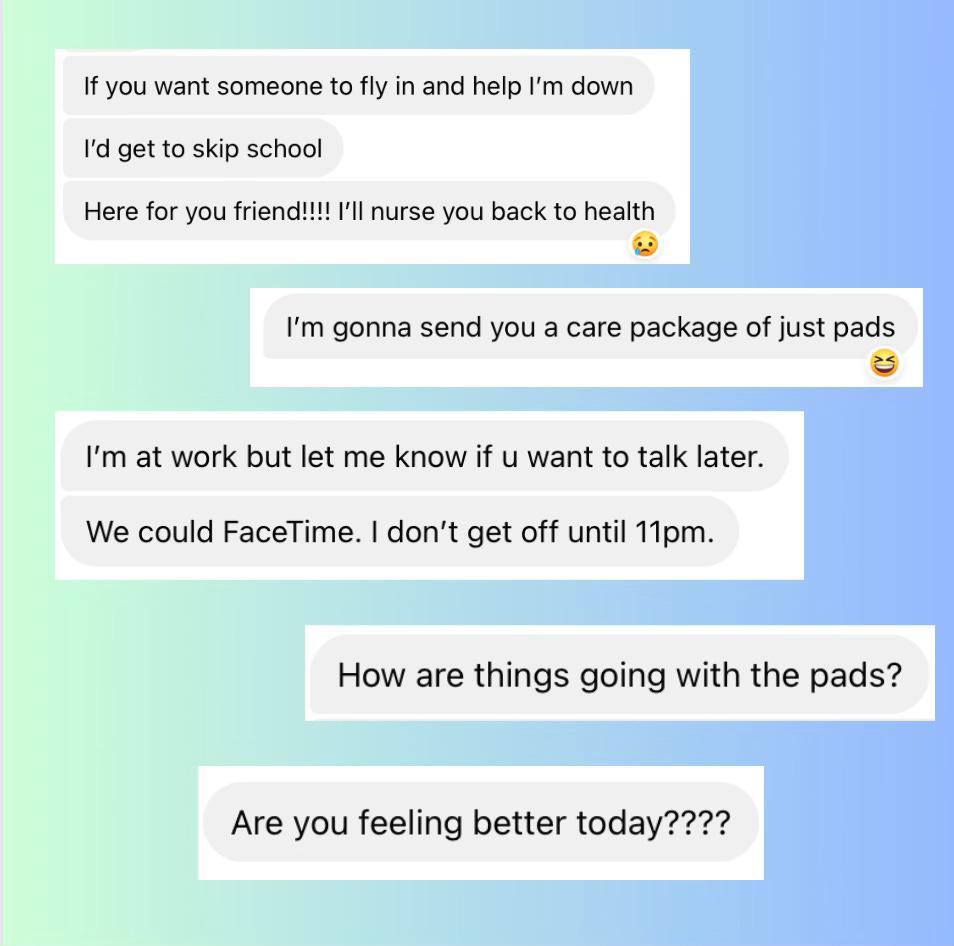

My memories, besides of the physical pain and embarrassment, are of my friends. My friend who flew from Texas to Chicago to sit at the clinic with me. My friend who waited while I bled in the shower. My friend who was the first person I told out loud, rather than over text. My friends who texted asking how I was feeling, how the pads were working, how they could help. My friends who wanted me to text them as soon as I had my appointment confirmed, who lent me their clothes when I bled through my own. My friends who I didn’t know at the time, but told years later. I wish I remembered more details about this part of the experience — the love I felt from friends in my most vulnerable moments.

In May 2022, when someone leaked that the Supreme Court planned to overturn Roe v Wade, I shared publicly for the first time that I’d gotten an abortion. I wrote and re-wrote an Instagram post, sanitizing it and removing “gruesome” details. The first slide was a screenshot of a tweet rather than my own words. People commented, thanking me. Two people messaged me — one that I was close to, one that I was not — sharing that they too had had abortions, and resonated with my feelings of shame and silence. Months later, at a wedding, a friend of a friend brought up my post. She’d had an abortion too. We talked candidly, while music blasted around us, about our experiences. Even though we didn’t know each other well, it felt good to talk out loud, to laugh and be pissed off about our experiences and pain.

My pregnancy, though brief, was awful. It was filled with intense nausea and pain. My abortion was awful too. I felt unprepared. I felt ashamed. I didn’t know of anyone who’d had an abortion. It was a long, stressful process to even make an appointment. But because of my friends, I didn’t feel alone. I have been saved time and time again by the loves of my life, my friends. Everyone should feel this. People getting abortions should be treated with respect and support and care. People should be able to access an abortion without driving hundreds of miles, without walking past protestors, without having to wait days after the first ultrasound, without having to call clinic after clinic after clinic for an appointment slot, without fearing they will be shot, without fearing that they or their providers will be arrested. Abortion should be a normal part of our systems and networks of medicine and care. And everyone getting an abortion should feel the deep love, support, and community that I felt from my friends.

This is a piece I’ve been working on slowly for five years. I began to write immediately after I got my abortion to preserve my memories and have slowly added to it over the years. As I was finishing the edits last week, the Supreme Court announced it would hear a case that may impact the availability of mifepristone, part of the two-drug sequence that I describe.

Thanks for reading.

Links

For Indigenous Peoples, Abortion Is a Religious Right by me and Rosalyn LaPier (published in Yes! Magazine and the book Aftermath: Life in Post-Roe America)

“Abortion is Sacred: Native perspectives on the overturning of Roe vs. Wade,” by Mara Cavallaro for El Tecolote — featuring an interview with yours truly!

Solidarity with Palestine: Free Resources and Further Reading from Verso Books